New Research Shows Impacts of Drought on National Park Visitation

National parks serve as conservation areas for ecosystems and as a haven for outdoor enthusiasts in the United States. Park visitation varies seasonally with favorable climate conditions for use and environmental features of parks, which vary from wildflowers to waterfalls. For example, visitors to high-elevation parks interested in wildflower viewing will favor the summer season when the flowers are in bloom. However, year-to-year variability in climate—including drought—may impact visitation patterns, as often recreation activities are directly (e.g., snow-based recreation, rafting) and indirectly (e.g., wildlife viewing, fishing) impacted by fluctuations in water resources.

While numerous studies have shown how visitors adjust recreational decisions due to weather, two NIDIS-funded studies led by researchers at the University of California, Merced examined relationships between park visitation and drought indicators. They found park visitation patterns changed with indicated drought conditions, and the impact of drought differed among parks, likely due to the different park characteristics and activities available in parks. These results may help park managers to plan for and manage drought.

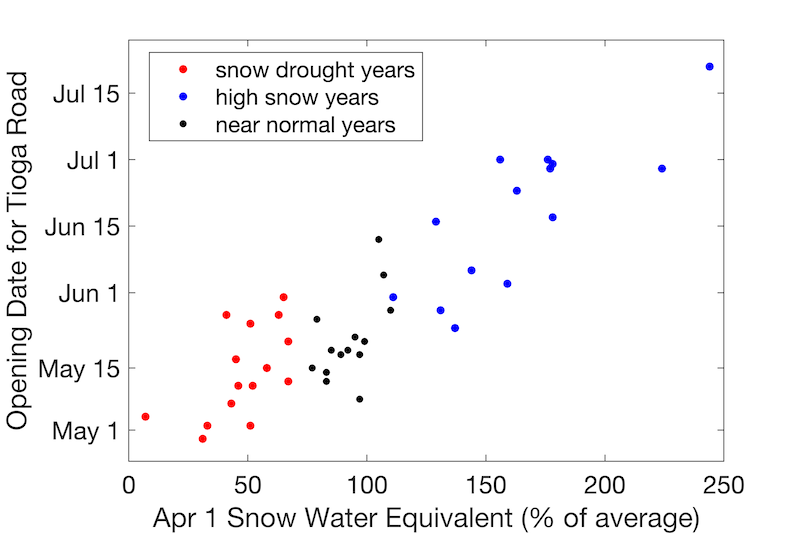

The first study, “Spring Snowpack Influences on the Volume and Timing of Spring and Peak-Season Overnight Visitation to Yosemite Wilderness,” examined relationships between overnight wilderness use in Yosemite National Park and spring snowpack. Long-term records of April 1 snow water equivalent at Tuolumne Meadows, an area in the western portion of the park, were used to classify past spring seasons into snow drought, near-normal, and high-snow years.

The opening of Tioga Pass, which provides access to the higher elevations in the park, exhibited a strong correlation with April 1 snow water equivalent. Snow drought years saw the road open about 4 weeks earlier than other years in the record, which enabled a significant uptick in high-elevation wilderness use in late spring and early summer. Notably, 2023 set a record for the highest April 1 snow water equivalent at the site in the station’s history dating back to 1930. In 2023, the Tioga road had its latest opening on record.

There was a park-wide increase in overall overnight wilderness use during snow drought years due to the dominance of wilderness use at high-elevation sites, but the authors also found a sustained increase in wilderness use at the lower-elevation park units during heavy snow years. This increase was likely a byproduct of both (1) the displacement of wilderness users within the park because high-elevation areas were inaccessible in heavy snow years and (2) more plentiful surface water supplies in late summer.

The second study, “Visitation to National Parks in California Shows Annual and Seasonal Change During Extreme Drought and Wet Years,” expanded upon the previous study by examining relationships between drought and park visitation across different national parks in California. Given the diversity of climates and associated water resources across the state, the authors considered how drought—realized through drought indicators such as the Palmer Drought Severity Index,, Evaporative Demand Drought Index, and Standardized Precipitation Index—was associated with visitation to coastal, mountain, and arid parks of the state.

In mountain parks, such as Yosemite and Sequoia-Kings Canyon, the authors found drought conditions negatively impacted park visitation during the summer and autumn months but were associated with increased use during the spring. Reductions in park visitation in summer and fall during drought years are likely associated with direct impacts to water-based recreation activities, such as reduced river flow or low water elevations in lakes, or indirect impacts from wildfires in the parks or adjacent areas that reduced access or degraded air quality.

By contrast, desert parks such as Death Valley and Joshua Tree saw reduced spring visitation during drought and increased spring visitation during wet years. At these parks, visitation peaks in the spring, when climate conditions are best for outdoor recreation and opportunities to see wildlife and blooming wildflowers. Drought reduces the number and diversity of desert plants and wildlife that are already narrowly adapted to scarce water resources. Wet winters contributed to super blooms in the California desert that drew more visitors, while drought conditions limited desert wildflowers and contributed to declines in park visitation.

These studies show a relationship between drought and visitor use in national parks and may be useful to park managers to guide park staffing levels to proactively adapt to drought conditions. However, there are still questions on the full impacts that drought has on visitors. Travel plans to some of these parks are made up to a year in advance, and drought conditions likely wouldn’t impact these visitors. Hence, the use of visitation numbers may under-represent the ways drought impacts user experience. For example, smoke from regional wildfires may reduce the activities available to visitors at Yosemite National Park during extreme drought conditions.

Learn more about this NIDIS-funded research project, Improving Drought Indicators to Support Drought Impact Mitigation for Natural Resource Management.