Flash Drought: New Reports Examine the 2017 Northern Plains Drought

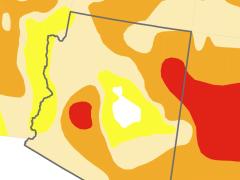

The 2017 Northern Plains drought sparked wildfires, destroyed livestock, and reduced agricultural production. Neither the drought’s swift onset nor its severity were forecasted. In May 2017, the region was mostly drought-free, and at least average summer precipitation was forecasted. By July 2017, North Dakota, South Dakota, eastern Montana, and the Canadian prairies were experiencing severe to extreme drought, resulting in fires that burned 4.8 million acres across both countries and U.S. agricultural losses in excess of $2.6 billion dollars. NIDIS and partners have published two reports to examine the evolution and impacts of the drought, as well as lessons learned, needs, and gaps.

The report, Flash Drought: Lessons Learned From the 2017 Drought Across the U.S. Northern Plains and Canadian Prairies, examines the historic 2017 drought event and its impacts, identifies opportunities to improve timeliness of and accessibility to early warning information, and identifies applied research questions and opportunities to improve drought-related coordination and management within the Missouri River Basin Drought Early Warning System. The needs that were repeatedly voiced during this study provide stepping-stones to improve outcomes in future droughts for this and other regions, including:

-

Invest in new and existing monitoring and observation networks, which would support the development of better indicators to provide early warning and allow decision-makers to better assess their drought risk and determine what actions to implement.

-

Improve the understanding of the relevant processes that inform forecast models in the region, which could improve seasonal forecasts to enhance drought preparedness.

-

Improve drought mitigation and response plans to consider trade-offs and actions that benefit both the human and ecosystem health and services, and put plans in place before a drought hits.

-

Maintain strong relationships and networks to share information between federal, state/provincial, tribal, and local stakeholders before, during, and after drought, thereby improving the process of drought preparedness and response.

The report, The Causes, Predictability, and Historical Context of the 2017 U.S. Northern Great Plains Drought, evaluates the causes, predictability, and historical context of the 2017 Northern Plains drought. The study was led by a team of weather and climate experts from NOAA’s Earth System Research Laboratory’s Physical Sciences Division and the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences located at the University of Colorado Boulder.

This study demonstrated that the rapid onset of the drought in the spring and summer of 2017 was mainly due to failed rains. Observed May-July precipitation over eastern Montana was the lowest on record and average precipitation over Montana, North Dakota, and South Dakota was the third lowest on record dating back to at least 1895. Failed rains led to the third largest soil moisture decline for any three-week period over eastern Montana since at least 1916.

Climate model simulations reveal that droughts with intensity similar to that of 2017 are 20% more likely due to anthropogenic influences. Anthropogenic influences increase the likelihood of droughts in July because of long-term reductions in soil moisture, also known as aridification. Aridification is forced by increases in evapotranspiration associated with rising temperatures.

Below average May-July 2017 precipitation was not predicted in advance of the season. Cumulative precipitation deficits were only predictable through sequences of up to three day forecasts. Sequences of longer than five-day forecasts provided no indication that the seasonal evolution of precipitation would be different from average.

Partners:

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

Bureau of Indian Affairs

Fort Belknap Indian Community

High Plains Regional Climate Center

National Drought Mitigation Center

NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory Physical Sciences Division

NOAA National Weather Service

NOAA Regional Climate Services

Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation

North Dakota Department of Emergency Services

North Dakota State University, North Dakota State Climate Office

Rattling Leaf Consulting

South Dakota Department of Environment and Natural Resources

South Dakota School of Mines and Technology

South Dakota State University, South Dakota State Climate Office

University of Montana, Montana Climate Office

University of Montana, Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research

University of Montana, Numerical Terradynamic Simulation Group

USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service

USDA Northern Plains Climate Hub