What Does Flash Drought Look Like in Your Region?

Flash drought can quickly deplete soil moisture and dramatically increase evaporative stress on the environment, leading to significant impacts on agriculture. A recently completed study, led by researchers from the University of Oklahoma and published in the journal Environmental Research Communications, performed a regional analysis across the United States to explore geographic differences of flash droughts.

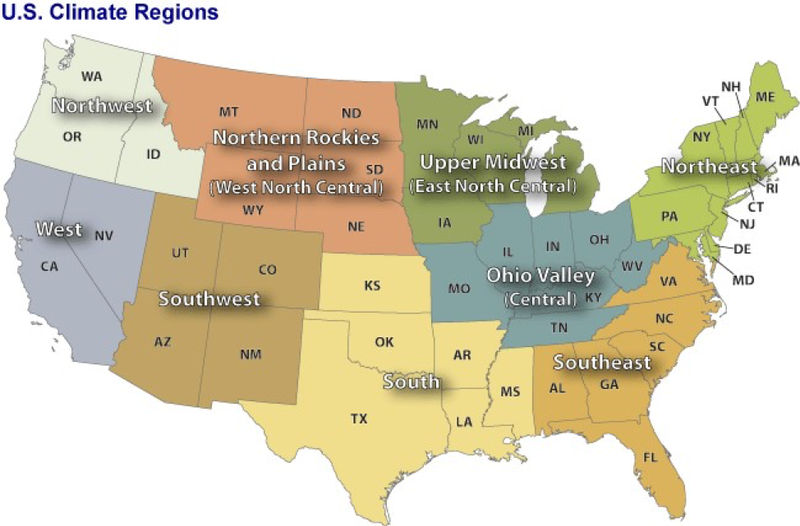

The overall goal of the research was to explore seasonal characteristics of flash droughts within the growing season, which runs primarily from March or April to October, and how they vary across the United States. Specifically, the analysis focused on quantifying the timing, intensity, preceding conditions, and the likelihood of persistence of flash drought to hydrological drought. To quantify the regional characteristics of flash drought events, the study focused on nine climate regions across the United States grouped by their climatologically similar characteristics (see figure below).

The study found differences in the frequency of flash drought across climate regions. In the Western US, which includes the Northwest, West, and Southwest climate regions, flash droughts occurred more frequently in May and June. The Northwest also saw an additional peak of flash drought frequency at the end of the growing season. In contrast, across the central and parts of the eastern United States, including the West North Central, South, East North Central, and Central regions, flash drought frequency peaked in July and August. Notwithstanding the recent fall 2019 drought in the Southeast, the frequency of flash drought in the Southeast region generally peaked in May. Flash drought intensity tended to increase towards the beginning of the growing season and then decrease in the latter portion of the growing season for all climate regions.

The study also quantified the preceding environmental conditions and potential post-flash drought persistence to hydrological drought for the various climate regions. Existing dry conditions increased flash drought risk for all of the climate regions. However, in five of the nine climate regions, including the West North Central, South, East North Central, Central, and Northeast, 37% to 47% of flash drought events occurred even when conditions appeared unfavorable for drought development in the preceding two months. This shows that flash drought can often occur even when there are no preceding signs.

Less than half of all flash drought events persisted to hydrological drought for all climate regions. However, 5% to 10% of all flash droughts in each climate region transitioned to the highest US Drought Monitor drought category (Exceptional Drought or D4).

Overall, the study provides a regional perspective into the climatological characteristics of flash drought in the United States. Why the regional differences exist could be the focus of future research as well as the drivers associated with flash drought development.

This study was supported, in part, by the NOAA Climate Program Office's Sectoral Applications Research Program (SARP), the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, the NASA Water Resources Program, and the USDA Southern Great Plains Climate Hub.