Snow drought persists in Pacific Northwest and Northern Rockies as climatological peak mountain snowpack approaches.

Key Points

- Warm and dry snow drought conditions have persisted, especially after a dry March, most prevalently in Washington, northern Idaho, Montana, and much of northern Wyoming. Some SNOTEL stations in this region are reporting record low snow water equivalent (SWE).

- Examining snowpack near its climatological peak provides more confidence (compared to early winter snowpack) in its role in the development of summer drought.

- An active March storm track favored the Sierra Nevada, central Great Basin, and Four Corners states, where little snow drought remained by the end of March. Snowpack in the Upper Colorado basin is critical for inflows into Lake Powell and Lake Mead, and this is the second consecutive year with above-normal SWE on April 1.

- April and May are critical months for monitoring the snowpack and preparing for possible rapid melt events during spring heat waves or rain-on-snow events.

Snow Telemetry (SNOTEL) snow water equivalent (SWE) values for watersheds in the western U.S. as a percentage of the 1991–2020 median recorded by the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). Only stations with at least 20 years of data are included in the station averages.

The SWE percent of median, in this figure and in the text, represents the current SWE at selected SNOTEL stations in or near the basin compared to the median value for those stations on the same date from 1991–2020. This map is valid through the end of the day March 31, 2024.

For an interactive version of this map, please visit NRCS.

Snow Telemetry (SNOTEL) and snow course snow water equivalent (SWE) values for watersheds in Alaska as a percentage of the 1991–2020 median recorded by the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). Only stations with at least 20 years of data are included in the station averages.

The SWE percentage of median, in this figure and in the text, represents the current SWE at selected SNOTEL stations in or near the basin compared to the median value for those stations on the same date. This map is valid through the end of March 2024.

For an interactive version of this map, please visit NRCS.

Drought is defined as the lack of precipitation over an extended period of time, usually for a season or more, that results in a water shortage. Changes in precipitation can substantially disrupt crops and livestock, influence the frequency and intensity of severe weather events, and affect the quality and quantity of water available for municipal and industrial use.

Learn MoreSnow drought is a period of abnormally low snowpack for the time of year. Snowpack typically acts as a natural reservoir, providing water throughout the drier summer months. Lack of snowpack storage, or a shift in timing of snowmelt, can be a challenge for drought planning.

Learn MorePeriods of drought can lead to inadequate water supply, threatening the health, safety, and welfare of communities. Streamflow, groundwater, reservoir, and snowpack data are key to monitoring and forecasting water supply.

Learn MoreIn a drought, lower water levels or snowpack can affect the availability of recreational activities and associated tourism, and a resulting loss of revenue can severely impact supply chains and the economy. Drought—as well as negative perceptions of drought, fire bans, or wildfires—may also result in decreased visitations, cancellations in hotel stays, a reduction in booked holidays, or reduced merchandise sales.

Learn MoreDrought is defined as the lack of precipitation over an extended period of time, usually for a season or more, that results in a water shortage. Changes in precipitation can substantially disrupt crops and livestock, influence the frequency and intensity of severe weather events, and affect the quality and quantity of water available for municipal and industrial use.

Learn MoreSnow drought is a period of abnormally low snowpack for the time of year. Snowpack typically acts as a natural reservoir, providing water throughout the drier summer months. Lack of snowpack storage, or a shift in timing of snowmelt, can be a challenge for drought planning.

Learn MorePeriods of drought can lead to inadequate water supply, threatening the health, safety, and welfare of communities. Streamflow, groundwater, reservoir, and snowpack data are key to monitoring and forecasting water supply.

Learn MoreIn a drought, lower water levels or snowpack can affect the availability of recreational activities and associated tourism, and a resulting loss of revenue can severely impact supply chains and the economy. Drought—as well as negative perceptions of drought, fire bans, or wildfires—may also result in decreased visitations, cancellations in hotel stays, a reduction in booked holidays, or reduced merchandise sales.

Learn MorePercent of Median Snow Water Equivalent

< 50% of Median

Current snow water equivalent (SWE) is less than 50% of the median SWE value for this day of the year, compared to historical conditions from 1991–2020.

50%–70% of Median

Current snow water equivalent (SWE) is between 50%–70% of the median SWE value for this day of the year, compared to historical conditions from 1991–2020.

70%–90% of Median

Current snow water equivalent (SWE) is between 70%–90% of the median SWE value for this day of the year, compared to historical conditions from 1991–2020.

90%–110% of Median

Current snow water equivalent (SWE) is between 90%–110% of the median SWE value for this day of the year, compared to historical conditions from 1991–2020.

110%–130% of Median

Current snow water equivalent (SWE) is between 110%–130% of the median SWE value for this day of the year, compared to historical conditions from 1991–2020.

130%–150% of Median

Current snow water equivalent (SWE) is between 130%–150% of the median SWE value for this day of the year, compared to historical conditions from 1991–2020.

>150% of Median

Current snow water equivalent (SWE) is greater than 150% of the median SWE value for this day of the year, compared to historical conditions from 1991–2020.

Percent of Median Snow Water Equivalent

< 50% of Median

Current snow water equivalent (SWE) is less than 50% of the median SWE value for this day of the year, compared to historical conditions from 1991–2020.

50%–70% of Median

Current snow water equivalent (SWE) is between 50%–70% of the median SWE value for this day of the year, compared to historical conditions from 1991–2020.

70%–90% of Median

Current snow water equivalent (SWE) is between 70%–90% of the median SWE value for this day of the year, compared to historical conditions from 1991–2020.

90%–110% of Median

Current snow water equivalent (SWE) is between 90%–110% of the median SWE value for this day of the year, compared to historical conditions from 1991–2020.

110%–130% of Median

Current snow water equivalent (SWE) is between 110%–130% of the median SWE value for this day of the year, compared to historical conditions from 1991–2020.

130%–150% of Median

Current snow water equivalent (SWE) is between 130%–150% of the median SWE value for this day of the year, compared to historical conditions from 1991–2020.

>150% of Median

Current snow water equivalent (SWE) is greater than 150% of the median SWE value for this day of the year, compared to historical conditions from 1991–2020.

Snow Telemetry (SNOTEL) snow water equivalent (SWE) values for watersheds in the western U.S. as a percentage of the 1991–2020 median recorded by the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). Only stations with at least 20 years of data are included in the station averages.

The SWE percent of median, in this figure and in the text, represents the current SWE at selected SNOTEL stations in or near the basin compared to the median value for those stations on the same date from 1991–2020. This map is valid through the end of the day March 31, 2024.

For an interactive version of this map, please visit NRCS.

Snow Telemetry (SNOTEL) and snow course snow water equivalent (SWE) values for watersheds in Alaska as a percentage of the 1991–2020 median recorded by the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). Only stations with at least 20 years of data are included in the station averages.

The SWE percentage of median, in this figure and in the text, represents the current SWE at selected SNOTEL stations in or near the basin compared to the median value for those stations on the same date. This map is valid through the end of March 2024.

For an interactive version of this map, please visit NRCS.

An updated, interactive version of this map is available through the USDA's Natural Resources Conservation Service.

An updated, interactive version of this map is available through the USDA's Natural Resources Conservation Service.

Drought is defined as the lack of precipitation over an extended period of time, usually for a season or more, that results in a water shortage. Changes in precipitation can substantially disrupt crops and livestock, influence the frequency and intensity of severe weather events, and affect the quality and quantity of water available for municipal and industrial use.

Learn MoreSnow drought is a period of abnormally low snowpack for the time of year. Snowpack typically acts as a natural reservoir, providing water throughout the drier summer months. Lack of snowpack storage, or a shift in timing of snowmelt, can be a challenge for drought planning.

Learn MorePeriods of drought can lead to inadequate water supply, threatening the health, safety, and welfare of communities. Streamflow, groundwater, reservoir, and snowpack data are key to monitoring and forecasting water supply.

Learn MoreIn a drought, lower water levels or snowpack can affect the availability of recreational activities and associated tourism, and a resulting loss of revenue can severely impact supply chains and the economy. Drought—as well as negative perceptions of drought, fire bans, or wildfires—may also result in decreased visitations, cancellations in hotel stays, a reduction in booked holidays, or reduced merchandise sales.

Learn MoreDrought is defined as the lack of precipitation over an extended period of time, usually for a season or more, that results in a water shortage. Changes in precipitation can substantially disrupt crops and livestock, influence the frequency and intensity of severe weather events, and affect the quality and quantity of water available for municipal and industrial use.

Learn MoreSnow drought is a period of abnormally low snowpack for the time of year. Snowpack typically acts as a natural reservoir, providing water throughout the drier summer months. Lack of snowpack storage, or a shift in timing of snowmelt, can be a challenge for drought planning.

Learn MorePeriods of drought can lead to inadequate water supply, threatening the health, safety, and welfare of communities. Streamflow, groundwater, reservoir, and snowpack data are key to monitoring and forecasting water supply.

Learn MoreIn a drought, lower water levels or snowpack can affect the availability of recreational activities and associated tourism, and a resulting loss of revenue can severely impact supply chains and the economy. Drought—as well as negative perceptions of drought, fire bans, or wildfires—may also result in decreased visitations, cancellations in hotel stays, a reduction in booked holidays, or reduced merchandise sales.

Learn MoreSnow Drought Conditions Summary for March 31

This update is based on data available as of Sunday, March 31, 2024 at 12:00 a.m. We acknowledge that conditions are evolving.

We are approaching climatological peak mountain snowpack across the West. Some areas, mostly at lower elevations and latitudes, already reached peak snowpack for the water year. Now is a critical time of year for water supply management as peak snowpack is one of the key variables used in forecasting spring and summer runoff. There is more confidence in the role of peak snowpack (compared to early winter snowpack) in the development of summer drought in basins that principally rely on snowmelt runoff. As the season progresses, forecasts generally become more accurate.

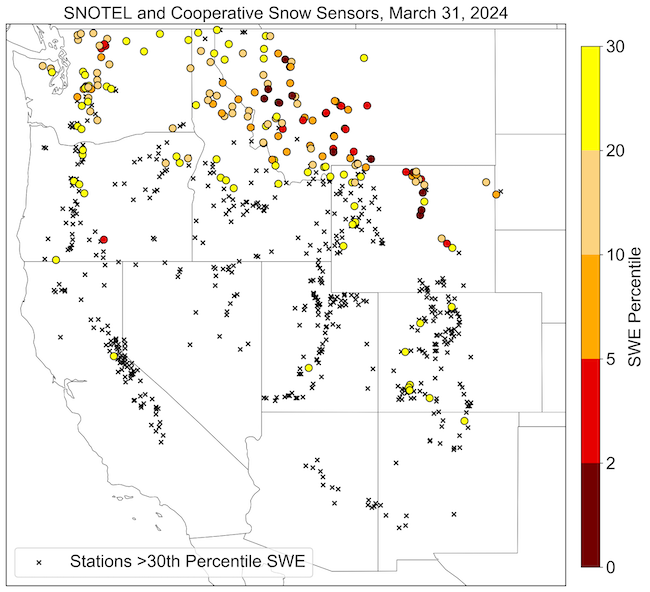

Snow drought conditions are currently most prevalent in Washington, northern Idaho, Montana, and much of northern Wyoming. Snow drought has persisted here for much of the season. A dry March worsened conditions, with some locations receiving less than 50% of average precipitation for the month. Conditions are particularly concerning in western Montana and in the Bighorn Mountains of northern Wyoming, where many SNOTEL stations are reporting record low snow water equivalent (SWE). An active March storm track favored the Sierra Nevada, central Great Basin, and Four Corners states, where little snow drought remained by the end of March.

Jump to conditions for your region:

- Rocky Mountain Snow Conditions

- New Mexico and Arizona Snow Conditions

- Cascade Range Snow Conditions

- Sierra Nevada and Great Basin Snow Conditions

- Alaska Snow Conditions

Stations with SWE Below the 30th Percentile in the Western U.S.

Key Takeaway: Snow drought conditions have persisted in Washington, northern Idaho, Montana, and much of northern Wyoming, where snow water equivalent (SWE) is below the 30th percentile at many SNOTEL stations. A dry March worsened conditions, with some locations receiving less than 50% of average precipitation for the month. Some SNOTEL stations in western Montana and in the Bighorn Mountains of northern Wyoming are reporting record low SWE.

Rocky Mountain Snow Conditions

Northern Rocky Mountains

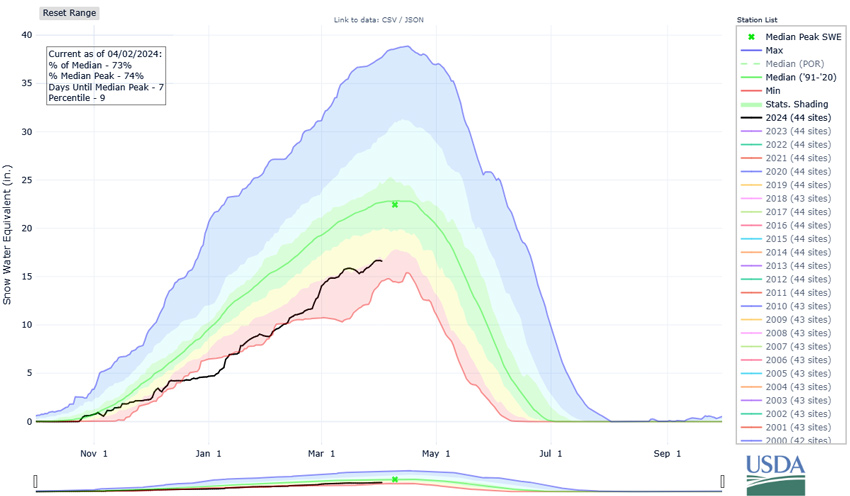

The most widespread and severe snow drought conditions are in the northern Rocky Mountains, from the U.S.-Canada border south into northern Wyoming. Snow drought has persisted in this region since the start of winter, driven primarily by extremely dry conditions. Periods of above-normal temperatures also contributed to the low snowpack, particularly at lower elevations.

Conditions are most extreme in western Montana (where ten SNOTEL stations and four April 1 snow survey sites are currently reporting the lowest SWE on record) and in the Bighorn Mountains in northern Wyoming (where four SNOTEL stations and three April 1 snow survey sites are reporting record low SWE). Many additional stations are reporting snow water equivalent (SWE) below the 10th percentile. The U.S. Drought Monitor currently depicts Moderate to Extreme Drought (D1-D3) across most of the northern Rocky Mountains, and worsening of drought conditions into spring and summer is of concern. Recovery to normal snowpack levels is unlikely this late in the season, but spring rains may mitigate drought development. The Montana Climate Office recently issued a press release detailing the severity of the drought and raising awareness about potential water shortages for agriculture and recreation.

Central/Southern Rocky Mountains

Conditions are much better further south in the Rocky Mountains, where all hydrologic unit code (HUC) 6 basins in southeastern Idaho, southwestern Wyoming, Utah, and Colorado are reporting above-normal SWE. One area reporting slightly below-normal snowpack is in the San Juan Mountains in southwest Colorado, where SWE at a cluster of SNOTEL stations currently is 81-92% of normal. Over the larger Upper Colorado River Basin HUC 2 region, which encompasses 130 SNOTEL stations, SWE is currently 114% of normal and 104% of normal peak. Normal peak snowpack in the basin occurs on April 6. Snowpack in the Upper Colorado basin is critical for inflows into Lake Powell and Lake Mead, and this is the second consecutive year with above-normal SWE on April 1.

Water Year Accumulated Snow Water Equivalent at Pend Oreille HUC 6 Basin

Key Takeaway: Snow drought has persisted in this region since the start of winter and has been driven primarily by extremely dry conditions with periods of above-normal temperatures, particularly at lower elevations. Snowpack is well below normal as we approach the climatological peak.

New Mexico and Arizona Snow Conditions

March was extremely wet in the mountains of Arizona and New Mexico, with many SNOTEL stations reporting greater than 200% of normal precipitation from March 1–31. The precipitation led to snowpack accumulation across the higher-elevation mountains after a period of dry and warm conditions in the second half of February. Almost all regional SNOTEL stations are reporting above-normal snow water equivalent (SWE) with SWE at many locations greater than 150% of normal. A few sites near the New Mexico-Colorado border are comparatively dry. SWE in the Lower Colorado River Basin typically peaks on March 3, and recent storms increased SWE in the basin back up to 101% of normal peak (199% of normal for the date). The heavy snowpack and wet conditions improved drought conditions, although Moderate (D1) and Severe (D2) Drought persists throughout the mountains and Extreme (D3) and Exceptional (D4) Drought is present along the New Mexico–Mexico border.

Cascade Range Snow Conditions

Snow drought continues to persist in much of Washington, with conditions generally improving to the south in Oregon. However, some areas of snow drought in Oregon that developed after the major snowmelt event in late January and early February persisted.

The past 30 days were extremely dry in the Washington Cascade Ranges from about Mt. Rainer north to the Canadian border, with SNOTEL stations reporting 40%-60% of normal precipitation. The dry month limited snow drought recovery, and many SNOTEL stations are reporting snow water equivalent (SWE) below the 15th percentile. Snowpack on Mount Gardner and Cougar Mountain, just west of Stampede Pass, has already melted, more than one month earlier than normal. At Cougar Mountain, the only years in which snow melted earlier since record-keeping began in 1982 were 1992 and 2015.

March storms had a greater impact in the Oregon Cascade Range. Much of the region received about 65%-85% of normal precipitation for March, with closer to 100% of normal precipitation near the California border. Most locations are currently not in a snow drought, but some isolated areas of concern remain. The melt event in late January had a major impact on seasonal snow drought, particularly at the lower-elevation stations. For example, Daly Lake in central Oregon gained about 6 inches of SWE from February 25 to March 14 but remained below normal as a result of the nearly 8 inches of SWE lost between January 18 and February 2. The situation in Oregon illustrates the transient nature of snow drought in some climates and the importance of event-based monitoring.

Sierra Nevada and Great Basin Snow Conditions

Snow drought in the Sierra Nevada has recovered slowly and steadily since early January, when the snowpack was about 50% of normal for the region. A series of small-to-moderate storms throughout January and February was punctuated by a major blizzard in early March, which deposited 5–7 feet of snow across the northern Sierra Nevada and several feet farther south in the Sierra Nevada. After a dry spell that lasted for about two weeks, storms returned around March 22 and persisted through the end of the month, leaving snow water equivalent (SWE) across the entire Sierra Nevada above normal on April 1.

SWE in most areas has continued to grow past peak SWE (i.e., the last week of March), which reduces the likelihood of early snowmelt and emergence of snow drought during the melt season. April and May are still critical months for monitoring the snowpack and preparing for possible rapid melt events during spring heat waves, which have occurred several times in the past few years.

Alaska Snow Conditions

April 1 snow survey data indicate that southeast Alaska is the primary area of snow drought concern in the state. Only seven snow survey points are currently available, but they span the northern panhandle south to Petersburg and all report below-normal snow water equivalent (SWE). The lower-elevation site near Juneau is reporting no snow, which has happened several times in the past, while the two higher-elevation sites are reporting 72%–78% of normal SWE. SWE at the single long-term SNOTEL site in the region, Long Lake, to the southeast of Juneau, is much closer to normal at 94%. The two snow survey sites near Petersburg are reporting 19% and 58% of normal SWE. Snowpack in south-central Alaska remains well above normal, as it has been for most of the season, with few snow drought concerns for the region.

October–March snowfall at the Anchorage Airport COOP station, 124 inches, was the second highest since record-keeping began in 1953. Around the Fairbanks area, snowfall has been close to normal for the season, and the few reliable reports from SNOTEL stations in the surrounding mountains indicate near-to-above normal SWE in the region.

* Quantifying snow drought values is an ongoing research effort. Here we have used the 30th percentile as a starting point based on partner expertise and research. Get more information on the current definition of snow drought.

For More Information, Please Contact:

Daniel McEvoy

Western Regional Climate Center

Daniel.McEvoy@dri.edu

Amanda Sheffield

CIRES/NOAA/NIDIS California-Nevada Regional Drought Information Coordinator

Amanda.Sheffield@noaa.gov

Britt Parker

NOAA/NIDIS Pacific Northwest Regional Drought Information Coordinator

Britt.Parker@noaa.gov

Gretel Follingstad

CIRES/NOAA/NIDIS Intermountain West Regional Drought Information Coordinator

Gretel.Follingstad@noaa.gov

NIDIS and its partners launched this snow drought effort in 2018 to provide data, maps, and tools for monitoring snow drought and its impacts as well as communicating the status of snow drought across the United States, including Alaska. Thank you to our partners for your continued support of this effort and review of these updates. If you would like to report snow drought impacts, please use the link below. Information collected will be shared with the states affected to help us better understand the short term, long term, and cumulative impacts of snow drought to the citizens and the economy of the regions reliant on snowpack.

Report Your Snow Drought Impacts

Data and Maps | Snow Drought

Research and Learn | Snow Drought